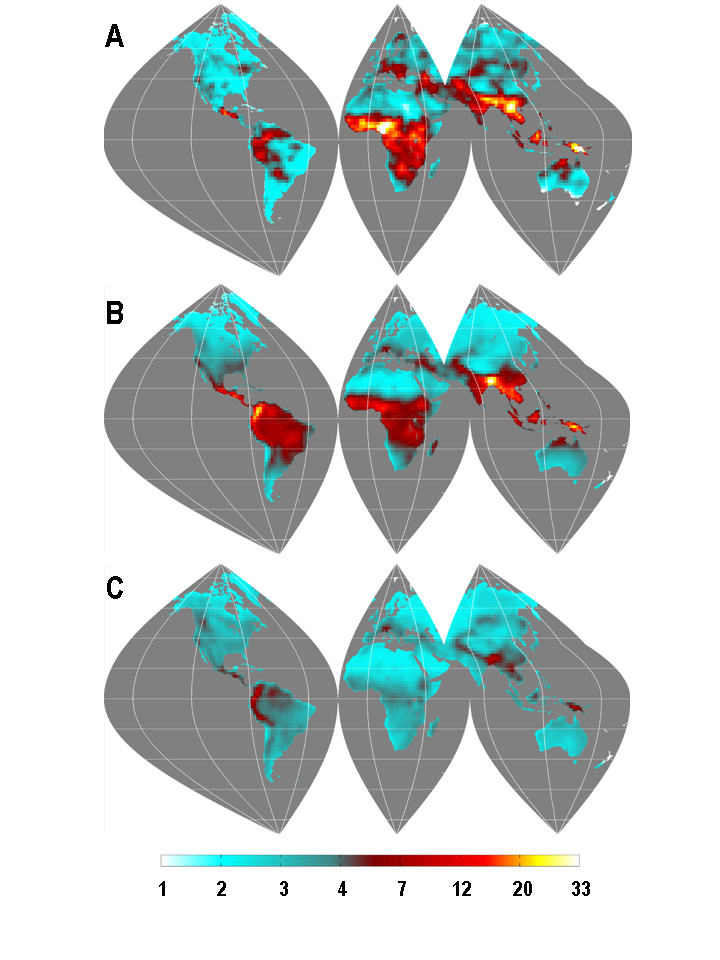

(A) Present linguistic diversity obtained from catalogued extant languages; (B) Past linguistic diversity inferred with our statistical model; (C) Future linguistic diversity predicted by extrapolating the American case.

On April 16th, the paper “River density and landscape roughness are universal determinants of linguistic diversity” co-authored by Jacob B. Axelsen and Susanna Manrubia, appeared on-line in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. This concluded a long investigation on the effects of environmental variables on linguistic diversity.

We were inspired by the many similarities between the heterogeneous distribution of linguistic diversity (LD) and that of biodiversity, which suggest that environmental variables play an essential role in their emergence. We investigated the significance of 14 variables: landscape roughness, altitude, river density, distance to lakes, seasonal maximum, average and minimum temperature, precipitation and vegetation, and population density. It turned out that landscape roughness and river density are the only two variables that universally affect LD. Overall, the considered set accounts for up to 80% of African LD, a figure that decreases for the joint Asia, Australia and the Pacific (69%), Europe (56%) and the Americas (53%). Differences among those regions can be traced down to a few variables that permit an interpretation of their current states of LD. The method we used can be applied to the cross-comparison of geographical regions, including the prediction of spatial diversity in alternative scenarios or in changing environments.

Our results have awaken the interest of the media: The Economist has just published a write-up of our paper with the appropriate title Mountains high enough and rivers wide enough. In the words of Lane Greene “Though not the main focus of their paper, Ms Manrubia and Mr Axelsen play with their data by applying the landscape-to-language fits of Europe and America to Africa and Asia, asking in effect, “What if the language-diversity development of Africa and Asia were to follow the path of Europe and the Americas?” The resulting “predicted” language density would see 3,700 of the world’s languages disappearing from Africa and Asia—startlingly close to the prediction that half of the world’s 7,000 languages might die out in the next century.“. We can play also the reverse game and infer what should have been America’s diversity before colonial times. Our results in this respect are summarized in the three maps shown, representing (A) the present, (B) the past (say some 1000 years ago), and (C) the future (some 500 years, probably less, from now) of World’s linguistic diversity.

The relevant role of rivers in (we believe) enhancing the emergence of new languages in the light of its correlation with current linguistic diversity has called the attention of Science Editors. Guy Riddihough highlights our work in the Editor’s Choice section with a note entitled Rivers of Words. You can see it in Science Magazine if you register (it is free) or can read it here.